Good | 2011

Good Magazine: “Radishes in Suburbia: Documenting urban growth and the end of a family farm”

By Thomas Gorman

When Matthew Moore returned to his family’s 1,000-acre carrot farm outside Phoenix in 2003, he was struck by how much the landscape had changed. During the seven years the 35 year-old spent studying sculpture in San Francisco, the city had expanded into the surrounding land. What was once a 30-minute drive into civilization was now a stroll across the road. A new Target big-box store broke ground nearby and a Wal-Mart is close behind.

Few cities epitomize suburban sprawl in the United States like Phoenix, Arizona. Over the last half century, the city has become the nation’s 6th largest metropolitan area, and with more than 4.1 million people, was one of the fastest growing until the housing collapse took some the wind from its sails.

Urban development nationwide has swallowed more than 23 million acres of agricultural land in the last quarter century. As a fourth-generation Arizona farmer, Matthew Moore is not the first to face the reality that one day soon, his family’s property will be completely engulfed by urban development.

In 2007, the city of Surprise, Arizona, released development projections for the area surrounding Moore’s farm. By 2030, his stretch of farmland is forecast to consist almost exclusively of mixed-use and medium density residential plots. Moore says he gets daily calls from speculators looking to snap up the property while the market is soft. “Every forecaster around here predicts that in 5 years, the market will be back,” he says. “It’s only a matter of time before we’re zoned out of existence.”

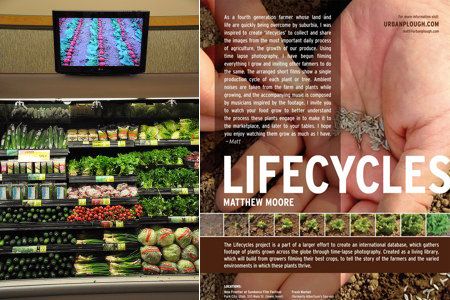

In order to save his family’s farming legacy, if not the farm itself, Moore set about documenting everything his farm produces. He set up solar-powered time-lapse cameras paired with weather-tracking systems, covering the entire growing period of his crops. He collected his compendium of short films into a project called Lifecycles.

Fittingly, Lifecycles had its feature debut in a supermarket. With support from the Sundance Institute’s New Frontier Program, Moore set up monitors above the produce section of a Fresh Market grocery store in Park City, Utah. He let the footage run on a loop for 10 days during the 2010 Sundance Film Festival.

While delicate growing patterns of squash, radishes, and broccoli unfolded on-screen, customers were invited to take a moment to reflect on the effort it takes to produce the surfeit of food to which Americans are accustomed.

Moore says he’d like to expand Lifecycles to stores around the country to spark a nationwide debate about farm policy. “I can get a raging conservative and an organic activist to shut up and watch transfixed for three minutes,” he says. “In the process, I can gently wipe their minds clean for a minute.”

The developer and the activist might take different cues from Lifecycles but Moore says if he can get people to more fully consider where their food comes from, that’s a start. “The plain basics are gone from the debate.” he says. “How is it revolutionary that people are just now re-learning where food comes from?”

Moore says he packs around 110,000 pounds of carrots a day, yet he’s never seen his produce in his area’s supermarkets. “It’s much like the art market,” he said. “I don’t know the buyers and the brokers don’t tell me.” His organic CSA is small but growing and he says his customers seem to take comfort in the personal connection. “The food tastes better because they know me,” he says.

With the initial success of Lifecycles in January, Moore launched a larger, more ambitious expansion of the project called the Digital Farm Collective. The idea would be to replicate his time-lapse cameras and weather stations at farms around the country, to record the particular regional varieties and inherited wisdom of independent farmers.

Moore hopes the eventual online omnibus could simultaneously educate consumers about the ecosystem of food plants while also giving producers access to the collective expertise of aging farmers.

He’s looking for start-up capital through the online crowd-sourcing site United States Artists, and he’s recruited a pair of farmers in California and Kentucky into his first class of contributors for this summer. Moore hopes to have recording equipment in the hands of six more farmers—including at least two in Arizona—by the end of 2011, as the next stage of his project’s world-wide expansion.

“I sometimes daydream that this project will one day find its way to some farmer in Peru,” Moore says. “That would go a long way towards re-centering the conversation.”